What's Inside The Page?

- Gill Partington

- Jun 4, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 6, 2019

The idea that a page has an 'inside' seems counterintuitive, but it's become the norm in the digital era. Reading text on an electronic device means we're looking at a screen that has incredibly complicated workings concealed behind it. However slim your kindle might be, it's really a container full of circuitry and microchips. There are things under the surface, making the page work. But even before we started reading on screens, the page was sometimes a complicated device, with mechanisms concealed inside it. The Speaking Picture Book in Cambridge University Library is one example. It's an odd contraption. It doesn't exactly speak but it does make noise. Its nursery rhymes about farmyard animals are accompanied by sounds operated by pull-cords, and each rhyme has a little arrow at the side of the page, indicating which one to pull. The sounds are not that convincing, but in 1893 when it was produced, it must have been a real marvel. It was produced in Germany by Theodore Brand, but this is the English language version, distributed by the publisher Grevel and co. (I mean the text is in English, rather than the animal sounds. I presume that these sounds were the same in throughout the book's various translations, although their spelling did change). Usually we talk about a book being printed, but this one was but manufactured: it’s a technical device that was subject to patent law. Brand made sure no one copied his invention, registering a German patent for the book in 1878, and a British patent a year later.

There are only a handful of these still in existence, and the copy in Cambridge University Library has only some of its sounds left, but its strings are too fragile to be pulled in any case. It’s the precursor of toys that are very common these days, using electronics to produce all kinds of noises. There are no transistors or microchips in the Speaking Picture Book though. The sounds are produced by a set of bellows. It looks like a thick book, but it's really a box. Only the top few pages with the rhymes are functional. Most of its 'pages' are just dummy ones, disguising a hollow shell containing the mechanism. It's a huge and cumbersome object, but mainly because most of it is just housing for the levers and pulleys that work the bellows.

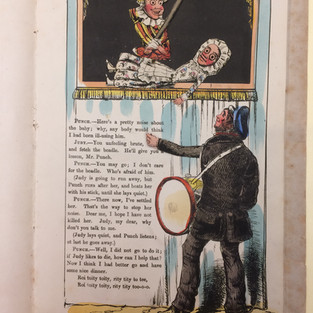

It may be a rarity, but it’s interesting because it's emblematic of a more widespread transformation of the page that took place in the late nineteenth century. Victorian children’s books frequently advertised themselves as ‘toy’ or ‘moveable’ books but also as 'mechanical books'. And indeed the page did become a mechanism of sorts. It began to sprout all manner of levers, wheels, strings and moving parts. Pulling a tab to make things happen was a device that emerged in the mid 1800s, but by the end of the century it had all kinds of applications, making illustrations move, making one picture 'dissolve' into another, or revolve. The page did things rather than simply being a medium for image or text. In one way this was a revival of an older tradition: ‘paper instruments’ were a common thing in the early modern period. Renaissance pages can be found with volvelles (rotating discs) and sun dials, three dimensional geometrical shapes and anatomical flap diagrams. But in the nineteenth century this kind of machinery migrated inside the page, where you couldn't see it.

The point about these paper mechanisms was that they were hidden, either fully or partially. Their workings were kept a mystery and the effects they produced a source of wonder for the reader. ‘Surprise’ is probably the most commonly used word in the titles of moveable books, closely followed by ‘magical’. The point is not simply that they move, but that it’s a kind of conjuring act. You can’t see how it's done. Consequently, the page is a complicated object in these mechanical books, both conceptually and topologically. Handling these pages, you can often feel that they are thicker than they should be, and that something is concealed inside. It's not really a single leaf but actually two leaves stuck together, forming an envelope for the moving parts. We might think of a page being defined precisely by its visibility, everything is on the surface because the page IS just a surface. But in this case it's doubled: there are actually four sides, but only two are visible, and there is a secret, hidden compartment. Like the Speaking Picture Book, these books have dummy pages whose real purpose is to be a housing for a mechanism. You can often see this in cases when books have been damaged. It's common to see pages where the moveable parts of illustrations have fallen off and there are missing limbs, but here's a picture of one of Lothar Meggendorfer’s mechanical pull-tab books, with its sealed pages split open to reveal its levers. They look like broken machines which of course, in a sense, they are. Even weirder, we’re also looking at an opening – a verso and recto – that was never meant to be seen.

Comments